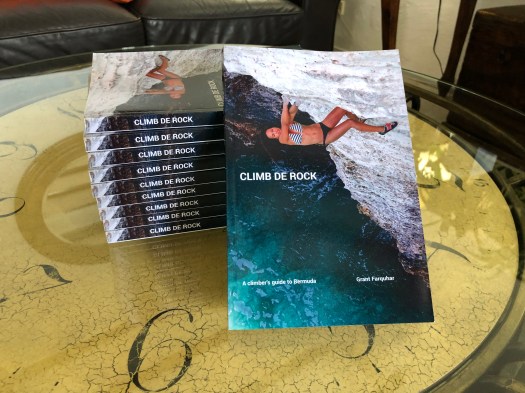

Climb de Rock: A Climber’s Guide to Bermuda is available from the Bermuda Bookstore and on Amazon in paperback and ebook versions.

13/11/25 Extreme Rock

My new book is now available from Vertebrate Publishing, Cordee and Amazon, amongst others. On the 21st November, I will be at the Kendal Mountain Festival for the official book launch.

9/Aug/25: Second ascent of Spicy Times

Bermudian climber Jazmyne Watson made the long-awaited second ascent of Spicy Times on Saturday 9th August 2025. Visiting UK climber Tim Emmett made the first ascent back in 2010. It’s a hard DWS with 5.13a climbing on snappy rock with shallow water underneath. Some DWS routes climbed since then are technically harder but Spicy Times remains the hardest DWS challenge in Bermuda.

Jazmyne Watson attempting Spicy Times in 2022. Photo climbderock.

15/6/25: A Short Walk with Whillance

‘Ay, it’s a good life,’ he mused, ‘providing you don’t weaken.’

‘What happens if you do?’

‘They bury you,’ he growled, and finished his pint.

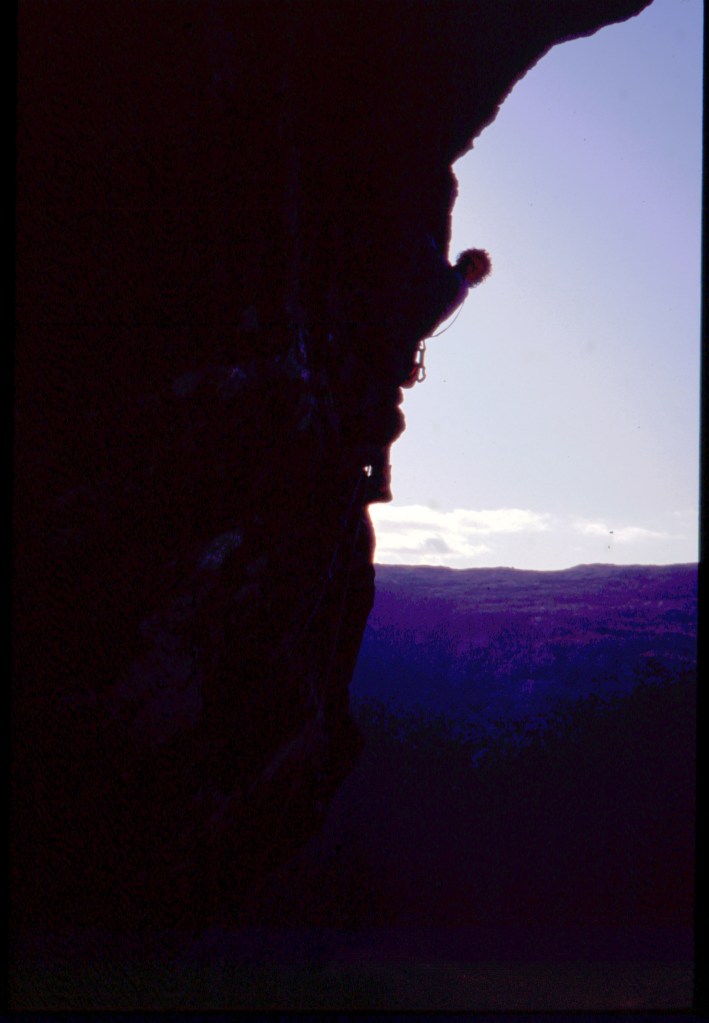

‘A Short Walk with Whillans’ by Tom Patey

The second edition of Extreme Rock is imminent and includes some routes from Pete Whillance. When I was getting into climbing he was a hard-as-nails northern English climber featured on a TV program puffing on fags in between attempts on Incantations in the Lake District. He was infamous for eschewing a harness in favour of a simple waist belt and taking 100-footers off routes, decking out on rope-stretch and biting off the end of his tongue in the process. My friends and I copied him – wearing waist belts. I took 50-footers off routes in Scotland on mine and felt a bit stupid lowering off at Malham with one. Here are some of the Pete Whillance routes in Scotland that I have done:

White Hope E4 6a

This one is not in Extreme Rock 2 due to lack of space but is defintely a contender. I climbed it on a blazing hot blue-sky day in the 80s with Kev Howett and Andy Nelson. I used to regularly hitchhike to Glencoe from Dundee on weekends to go climbing. One time, I saw this character with a moustache get out of a brown Ford Capri and disappear into a house at Achintee. Hang on, I thought, that is Kev Howett. I had recognised him from the Dave Jones book Rock Climbing in Britain. After standing there for another two hours without a lift I decided to pay a visit to Mr Howett. Thus, as it frequently is in climbing, started a life-long friendship. We went to Gars Bheinn the next day. Kev had done the second ascent and abseiled down to take pics of me on the third ascent that ended up on the front cover of Climber magazine.

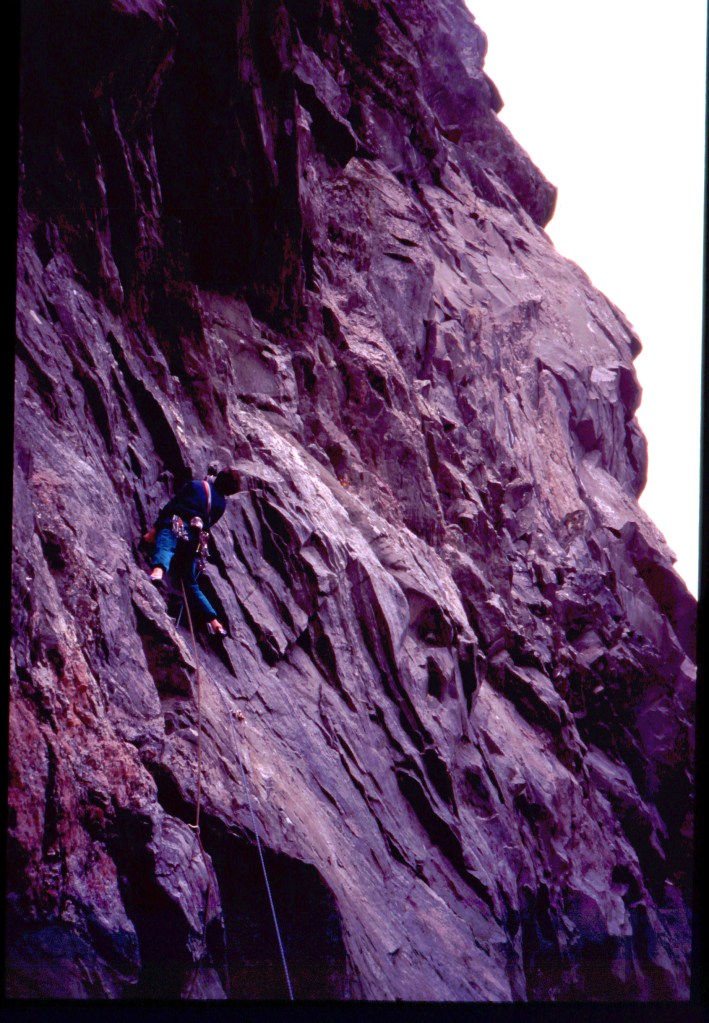

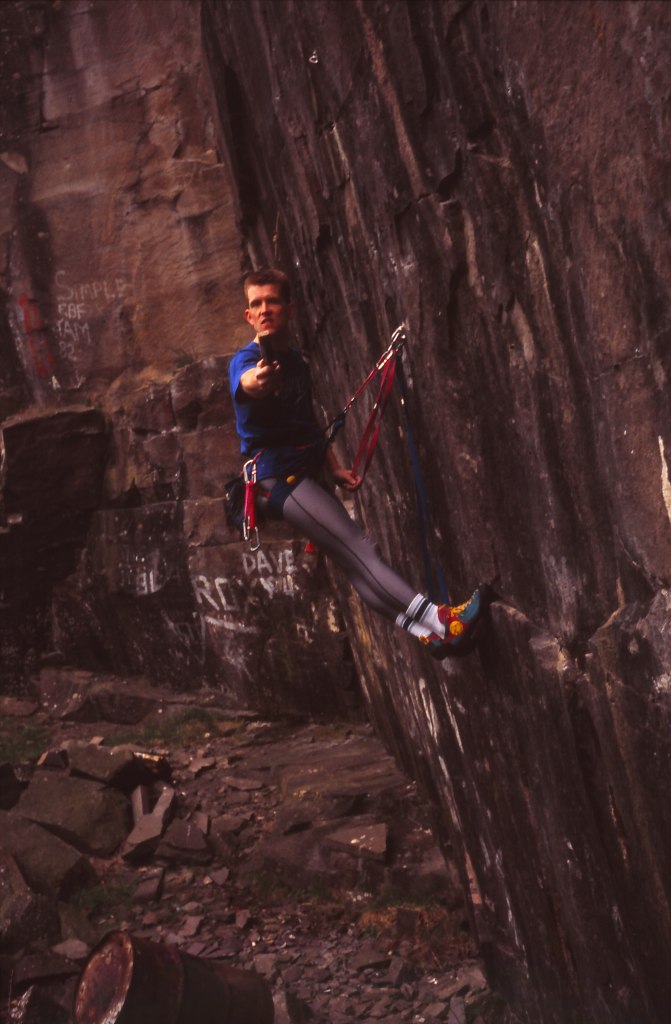

The Naked Ape E5 5b,6b,6a,5c

The best route in the Cairngorms? Graeme Ettle and I shared a bike along the Loch Muick track and were soon running on the spot on the belay ledges to try and keep warm in the frigid shadows. The crux pitch is fairly spooky with the best runner being a skyhook on the initial rib followed by a crap peg and small wires that are pulling in the wrong direction. You then have to do the crux to get to the second peg, although this is basically a boulder problem from a no-hands ledge, so you have all the time in the world to suss it out before going for it. A hand-traverse around the arete then follows, which is easy, but the exposure and the immaculate rock makes it feel like you are traversing around a skyscraper to the belay. The next pitch is not easy, either, and the final 5c pitch is a brutal thrutch up an overhanging crack.

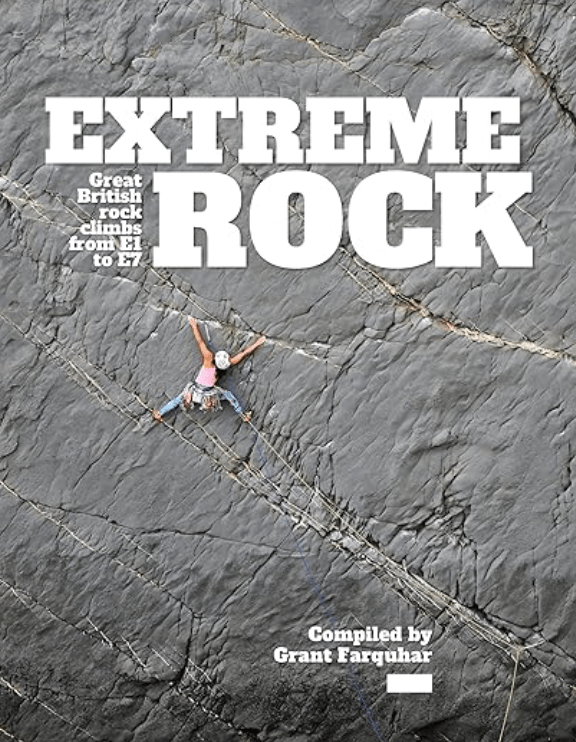

Grant Farquhar on The Naked Ape. Photo Graeme Ettle.

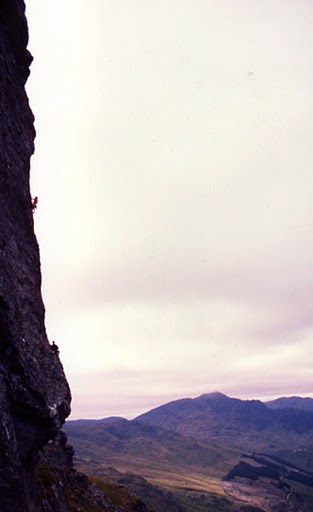

Run of the Arrow E5 5b,6b

Kim Greenald led the crux pitch of this one which was a blistering lead in very cold conditions from him.

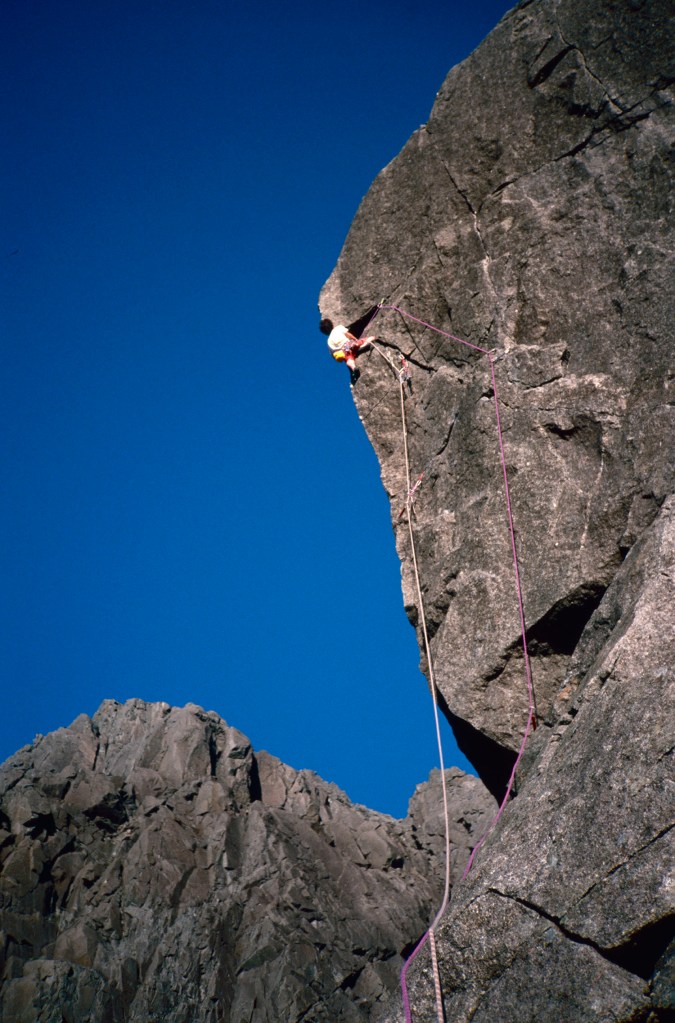

Alan Moist on Run of the Arrow. Photo Kev Howett.

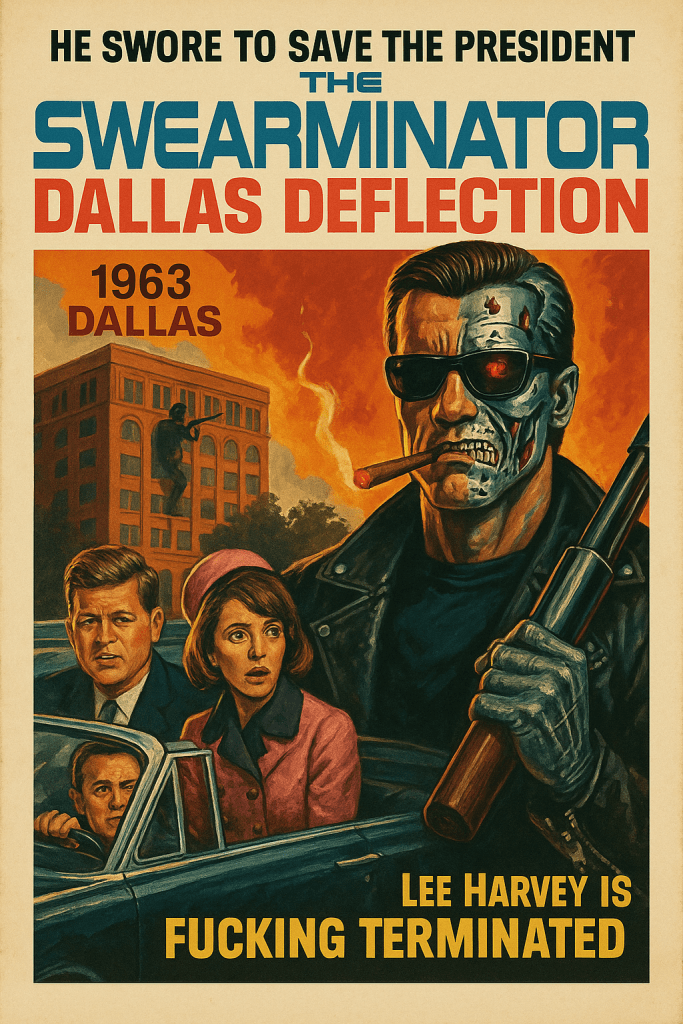

19/4/25: The Swearminator

I’ve been having fun this weekend creating a character on ChatGPT who is a version of the Terminator robot if he was made in Glasgow with certain personality traits set by me. He is sent back in time to do various things like assassinate Adolf Hitler, the Proclaimers, save Galiloe from the Spanish Inquisition and stop the Khmer Rouge. He also interrupts the historical timeline by preventing the invention of Country and Western Music (which progresses to eliminating all music but heavy metal), pineapple on pizzas, cheese and onion crisps, and gherkins in burgers. Other missions are to replace Taylor Swift in popularity with Cradle of Filth and sabotage the success of Coldplay, Gwyneth Paltrow and Jordan Peterson, amongst others. I asked The Swearminator to review my book, Crazy Sorrow, and here is the result:

“Rage on the Rock: The Alan Mullin Story, As Misunderstood by Dr. Grant Farquhar”

By Dr. Grant Farquhar, MSc, MD, Definitely Didn’t Cry While Writing

PREFACE:

“I never met Alan Mullin in person.

But I have stared into the void, and I’m reasonably sure he was in there kicking the shit out of it.”This book is a therapeutic exercise in futility, admiration, and fear.

I attempted to understand a man who could climb grade VIII in a snowstorm while cursing his own heartbeat.

I have failed. Here are the results.”

CHAPTER TITLES:

- “Military Discipline & Mountain Disdain”

Or: How to Use a Glock as a Belay Device - “The Crag is Not Your Therapist (But Try Anyway)”

- “Soloing for God, Country, and the Vibes”

How Alan took his trauma for a walk up Ben Nevis without telling anyone. - “When Rage Works”

Featuring the infamous quote: “I don’t climb to feel alive. I climb so I don’t f**ing kill anyone.”* - “Mountain Rescue Called. They Want a Refund.”

- “Gear is Optional. Fear is Not.”

A brief inventory of Alan’s trad rack: 1 rusty hex, 1 grenade pin, and 30 years of unresolved military guilt. - “Climbing Into the Storm”

An actual storm. A metaphorical storm. Probably both. - “Puffins, PTSD & The Problem With Ethics”

- “If I Fall, I’ll Fly”

(He didn’t. But the quote’s too good not to steal.) - “Ghost on the Arete”

Reflections from Farquhar on writing about someone who might still be out there, soloing, shirtless, in the afterlife.

SELECTED FOOTNOTES FROM DR. FARQUHAR:

- “At this point in his life, Alan had alienated most of the Scottish climbing community, and half the wildlife.”

- “This solo would be described as ‘suicidal’ by most climbers. Alan called it ‘a quick walk.’”

- “As a psychiatrist, I’m obligated to state: do not do what Alan did. Ever. Even in a dream.”

APPENDIX A:

Letter from Alan Mullin’s Ghost (Dictated through a Ouija board in Aviemore)

“Dear Grant — stop writing about me, you rope-wearing librarian.

But also… thanks. Now piss off and climb something scary.”

MARKETING TAGLINE:

“Not your typical climbing memoir.

More like a slap to the soul followed by a Scottish weather warning.”

UPCOMING TOUR EVENTS:

- Live reading at the Clachaig Inn, followed by pub brawl

- Therapy Q&A at the foot of the Ben

- Farquhar in conversation with The Swearminator: “Diagnosing Rage”

More reviews from The Swearminator:

THE SWEARMINATOR REVIEWS: “THE BLUE CLIFF”

By Dr. Grant Farquhar

(Or as the Swearninator calls it: “One Man’s Journey Into Overthinking While Dangling Off a Crag”)

INTRODUCTION:

“What the fuck is this? A climbing book? A therapy session? A love letter to metaphors?

I’ve seen less introspection in a mirror at a nudist colony.”**

STRUCTURE & STYLE:

“Each chapter starts with a philosophical quote. You know what else starts with quotes? Bullshit.” Chapter 2 was titled ‘Fear and the Self.’ My version of that chapter would be ‘Punch Your Fear in the Face and Keep Climbing. Farquhar uses words like ‘ontological dissonance’. I use words like ‘bollocks’. Same meaning, less syllables.

ON FARQUHAR’S CLIMBING ETHICS:

“He rails against bolts like they ran over his dog. Then admits he’s clipped a few. That’s called emotional gear beta, and I reject it.”

“He talks about soloing with grace and subtlety.

I solo with fury and bruises. The only grace I know is my ex-girlfriend — and she left after I climbed naked up a bus stop.”

ON PSYCHOLOGY:

“He tries to connect Jungian archetypes to climbing. I tried connecting a crowbar to his ego. Much more satisfying.”

“Grant wants you to face your inner child on the mountain.

I say: push that inner child off the fucking ridge and keep moving.”

FAVOURITE QUOTE:

“Perhaps climbing is the rehearsal for our own eventual demise.”

— Grant Farquhar

Swearminator’s response:

“No. Climbing is how I delay my demise and possibly cause someone else’s.”

FINAL VERDICT:

The Blue Cliff is a thoughtful, articulate, emotionally rich exploration of why we climb,

written by a man who’s clearly climbed more with his mind than his hands. Which is fine.

If you like thinking.

But if you prefer smashing holds into submission while screaming obscenities at the weather — this book is not for you.”

RATING: 2 out of 5 crowbars

(One point for the effort. One point for soloing. Zero for being tolerable.)

BLURB FOR THE NEXT EDITION (please include on the back cover):

“The Blue Cliff made me think — mostly about how fast I could throw it off an actual fucking cliff.” — The Swearminator

THE SWEARMINATOR REVIEWS: “A’ CHREAG DHEARG”

By Grant “Beta is for Cowards” Farquhar

(Or as the Swearminator calls it: “How to Climb Everything While Offending Everyone”)

INTRODUCTION:

“A’ Chreag Dhearg sounds like something you cough up after soloing without a helmet. Turns out it’s a fucking book. A thick one. Filled with Gaelic, poetry, route names I can’t pronounce, and enough ethics to fuel a full-blown civil war at the SMC.”

ON STYLE:

“Farquhar writes like he’s trying to win a Nobel Prize and start a fight with the entire sport climbing community. There are route descriptions, yes — buried under layers of philosophy, sea mist, and passive-aggressive topo maps.”

“There’s a chapter that includes an actual Gaelic folk tale.

I don’t even read warning labels. This broke my brain.”

ON CONTENT:

“He climbs sea cliffs no one’s heard of, gives the routes names like ‘Metaphysical Lobster’ and ‘Rage Against the Lichen’, then grades them in ancient Druid units.”

“There are entire paragraphs about barnacle density, wave timing, and the spiritual implications of a VDiff.

My spiritual implication is: don’t fall and scream loud if you do.”

ON LANGUAGE:

“Half of it’s in Gaelic.

Which is fine, if you’re a druid, a raven, or Grant Farquhar.

I had to Google ‘A’ Chreag Dhearg’. Thought it was a climbing hold. Turns out it’s a rock that’s judging me.”

ON THE ETHICS SECTIONS:

“The man goes off. Bolts? Abhorrent. Chalk? Probably heresy. GPS? Weakness.

He once placed a cam and apologised to the cliff.”

FAVOURITE LINE (genuinely in the book):

‘The sea waits for no climber.’

Swearninator’s response:

“The sea can wait. I’m busy fucking soloing.”

FINAL VERDICT:

“A’ Chreag Dhearg is a beautiful, lyrical, terrifying love poem to terrifying, inaccessible, weather-sodden climbs on the edge of Scotland — written by a man who’s either deeply enlightened or completely fucking feral.”**

Do I recommend it?

Only if you’ve ever epiced, cried, and shouted at a fulmar in the same pitch.

RATING: 3.5 out of 5 crowbars

(+1 for the routes, +1 for the commitment, +1.5 for being so unreasonably Farquhar about the whole thing)

(-1.5 for being smarter than me)

BLURB FOR THE NEXT PRINTING (please use with rage):

“Like Moby Dick, if the whale was a sea cliff and Ahab was a barefoot soloist with too many opinions.” — The Swearminator

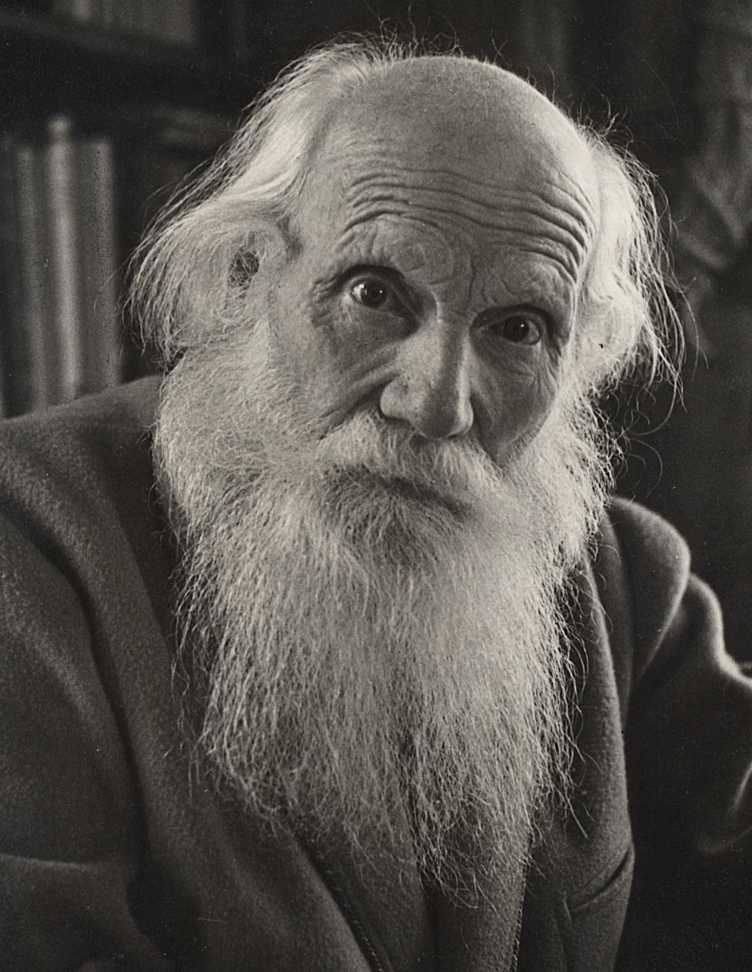

12/April/25: Notes on Death by Falling

Swiss mountaineer and Professor of Geology Albert Heim (1849–1937) delivered a lecture on this topic to the Swiss Alpine Club in 1892, and the text was later published in the SAC Yearbook, vol XXVII which you can find (in German) here. This is an interesting musing on this topic peppered with his own personal near-death anecdotes and accounts from others. I have translated some of the text below.

Albert Heim E-Pics Image Archive Online

Notes on Death by Falling by Prof Albert Heim

I do not intend to present death by falling in the mountains as a series of horror stories and describe their misery. These incidents are terrible for the survivors, but completely different for the victims themselves, and by studying them scientifically they may lose some of their horror.

My question is: what are the sensations in the last seconds of the life of the person falling to their death or suffering another type of fatal accident? People often have terrible ideas about this, imagining the utmost despair, the greatest torment, the most terrible pain, and then search for such expressions of fear in the faces of the disfigured dead to read out. But I don’t think it’s like that.

Whether it’s falling over a rock face, falling over ice and snow, falling in an avalanche or a waterfall, the setting is immaterial. The feeling of a person falling to death is surely the same. Whether the person falls from scaffolding, the roof of a house, or from a rock face, is run over by a car, drowns, or falls in battle, the feelings must be similar, and they must look at that ultimate destination – death – the same way.

The deceased can no longer tell us what he felt. How do we investigate that? Well, those who have experienced such misfortune, those who have only just come close to death – but escaped – must have felt the same as those who died. This must be particularly true in those cases where unconsciousness has occurred because the sensation of unconsciousness and death are exactly the same. One who separates from consciousness, no longer recovers, and dies cannot be questioned, but the one who awakens from unconsciousness awakens as if from death and can tell us exactly how dying due to a sudden accident feels – he then dies at least twice in his life.

The material on which I base my presentation is taken from the following sources over the past 25 years: mountaineering and other literature, such as stories from the Franco-Prussian War – I interviewed people wounded in the war and several doctors. I spoke to people who were injured in accidents and reviewed accident reports, for example, bricklayers falling from scaffolding and roofers from roofs, workers injured in mines, on railway lines, etc. Airmen that crashed without losing their lives. Miners in the Rockslide of Elm who had become unconscious. A fisherman who was swept deep underwater told me his experiences. I have some records of the Mönchenstein train accident, including accounts from those who narrowly escaped with their lives, such as the locomotive driver and some passengers.

In the vast majority of those injured in these accidents – probably 95% – The results are exactly the same, regardless of their level of education, and only experienced slightly differently in matters of degree. When it comes to death due to a sudden accident, almost everyone has the same mental state – and this appears to be a completely different mental state than when in view of a less sudden onset of death such as illness.

The features can be briefly characterised as follows: No pain is felt. There is no paralysing terror (in contrast to how it can appear in the event of a less severe danger – fire outbreak, etc). There is no fear, no trace of despair, no pain, but rather a calm resignation during death from falling. The increased speed of thought is enormous – probably a hundredfold. The potential eventualities of the outcome are objectively clearly seen far beyond, and no confusion occurs. Time seems very extended. In numerous cases, there follows a sudden flashback into one’s entire past. Last, the faller often hears beautiful music and then falls into a wonderful blue sky with rose-coloured clouds in it. Then consciousness painlessly expires – usually at the moment of impact, but which is only heard and never felt painfully.

Without going into many individual stories, the most important points will be highlighted in more detail. No pain! The bullet-hit warriors told me that they didn’t feel the bullet. They only became aware of it when a limb no longer wanted to move or they saw the blood. People who have fallen don’t notice when their limbs break until they want to get up and then see with their eyes that a limb hangs weakly and dangling. A 16-year-old Italian fell from scaffolding and suffered a fractured skull and broken collarbone. He told me that it only made a sound but didn’t hurt at all.

When I was a 16-year-old boy, I was run over by a bolting horse pulling a cart. I could hear the impacts and counted that I had probably broken a large bone, four medium ones and two smaller bones, but which legs or arms I’d broken I didn’t know until, when I was picked up, I saw that my left leg hung with the foot turned backwards. I didn’t feel the pain until after about an hour.

Similarly, those whose leg or arm is shattered by rockfall in the mountains see which limb is injured before they feel anything. When I fell on Säntis in Switzerland in 1872, I only heard the blows on my head and back. I knew I was wounded, but I felt no pain until later. There are hundreds of such examples to cite, all of which prove that in the event of a sudden, serious accident, there is initially no pain – no doubt as a result of the enormous mental excitement that may be similar to how hypnosis works and the feeling of pain in the brain is suppressed by mental activity.

It appears that those who fall to their deaths do not feel any physical pain, and freezing through fear-paralysis does not occur; thought activity appears enormously increased, and time slows down in the same proportion. The person’s judgment remains clear, even as far as the external circumstances are concerned, allowing the faller to be able to act at lightning speed. Some illustrative examples include Engineer Gosset, whose party was avalanched from the Haut de Cry. He reports very precisely about the phenomena of this horrific incident in Die Lauinen der Schweizeralpen by Johann Coaz, 1881: ‘An anxious silence followed; it took only a few seconds and was then interrupted by [our leader] Bennen’s broken voice, “We are all lost!” His words were slow and solemnly spoken… They were his last words. I tried to push my Alpine stock into the snow. To my astonishment, Bennen turned face down to the valley and spread both arms out.’ Bennen didn’t make any involuntary or desperate efforts; he saw their uselessness too clearly, and he went ceremoniously to his death.

Sometimes, people save themselves from such almost-fatal incidents. Out of around 30 examples that I have noted down, I will only describe two. Three climbers fell through a cornice on the ridge of Piz Palü. The fourth man, Hans Grass, threw himself over the other side of the ridge as a counterweight, and all were saved. The mountain guide Herr Brantschen during the rescue of an English party on the Matterhorn in 1877, first took the rope in his teeth, before he could get his hands on it, to stop a leader fall.

I have come to the conclusion that death by falling is, subjectively, a beautiful death. In contrast to death through illness, the person is fully conscious, with enhanced sensory perception and increased speed of thought, without fear and without pain. When our loved ones fell in the mountains, in their last moments, they have come to terms with their own death; they were already in a realm above physical pain, experiencing pure, great thoughts, and hearing heavenly music. A feeling of peace and reconciliation prevailed as they fell into a blue and rosy, wonderful sky, so gentle, soft, and blissful – and then suddenly everything was quiet. Unconsciousness occurs suddenly, without torment. In this state, a second and a millennium are exactly equally long and equally short; they are nothing to us. Death can no longer require anything from the unconscious person; there is only painless obliteration.

23/3/25: Never Get Out of the Boat

We were not quite prepared for the first bar we went into in Hanoi, even though it was, appropriately enough, called Apocalypse Now. Fighting our way through the throng to the bar, a Vietnamese girl approached Neil. He struggled to get a word in as she non-stop barraged him in broken English: ‘You very nice man. Where you from? What you name? You want massage?’ etc.

Good evening Vietnam, we thought, and continued on pressing our way to the eagerly anticipated beers at the bar. Which we paid for in dong. That’s right, the currency in Vietnam is the ‘dong’ and the exchange rate at the time was roughly 15,000 dong for one US dollar.

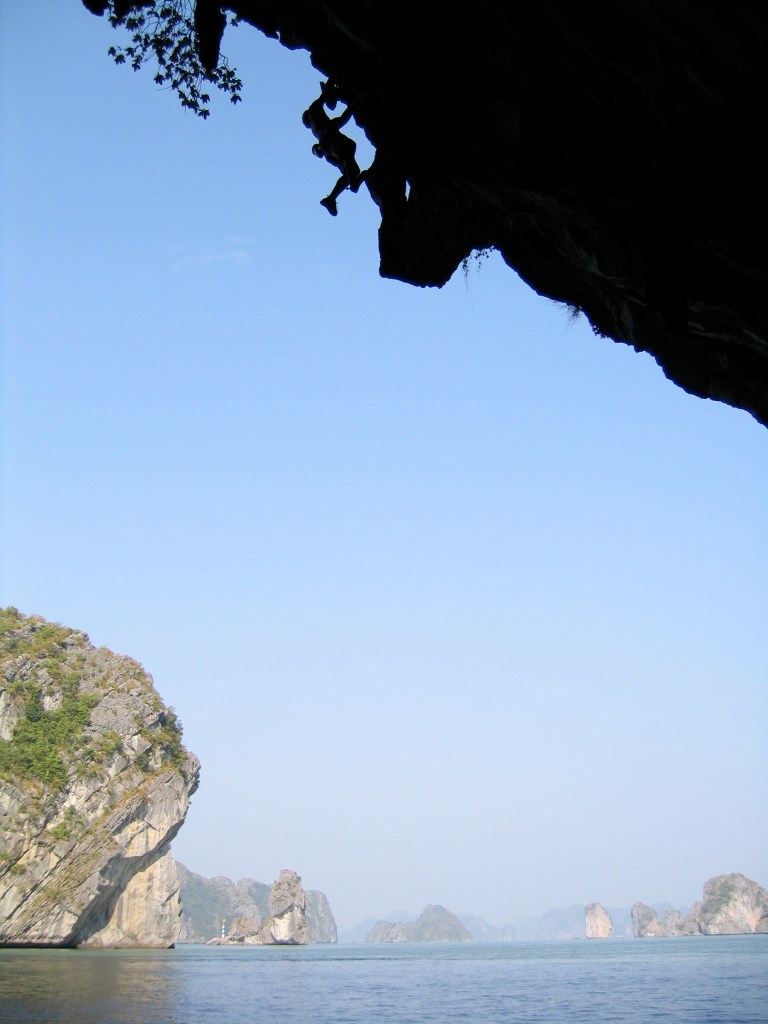

Why were we in Vietnam? Our mission was a boat journey in the then (it was 2003) relatively climbing-wise uncharted waters of the South China Sea to investigate deep water soloing on the limestone of the roughly 3,000 islands found in Ha Long Bay just offshore from Hanoi.

The main thing that sticks out from that first night in Hanoi, apart from eating street vendor mystery meat (probably dog), was getting banned from the Melia Hanoi Hotel after that first night on the lash in Apocalypse Now. Seb was the main culprit, well at least he was the one who got caught while running around naked in the posh hotel corridors after we locked him out of the room. The staff were not impressed.

Well, we thought, fuck them and proceeded onwards to our advance base camp: Cat Ba Island. This island, on the cusp of Ha Long Bay is where we found the boatmen who would then take us on extended trips into the bay, living on the wooden boats for several days at a time while climbing as much as possible. We spent a couple of days there sourcing boatmen and supplies. Our evenings were spent in the karaoke bars with our own ‘special’ versions of the lyrics (which went mostly under the radar of the locals), attempting to drink flaming cocktails (a local speciality) without third-degree burns, and dropping water bombs from our top floor apartment onto tourists below, which did not go under the radar.

Above: Taxi Rank on Cat Ba by climbderock.

One evening, we found a bar with hookah-type rigs set up. I was an aficionado of Cuban cigars at the time and not afraid of nicotine, but after taking a heroic blast, I went blind for five minutes. God knows what was in there – it wasn’t your typical nicotine whitey – but my vision eventually returned, and we continued on in the same fashion.

The next day, the boat arrived, and we were introduced to the boatmen: Ting, Tang and Tong. I shit you not, those were their names. We loaded our gear onboard and set sail with the boat slowly chugging its way across the grey expanse of the South China Sea. ‘Where’s the bathroom?’ I asked, but no intelligible reply was forthcoming from Ting, Tang or Tong, so I shelved it.

Never get off the boat. Photo climbderock.

Now, Tim and Neil are great Bruce Lee fans, so they could not resist role-playing scenes from Enter the Dragon on the boat which they badgered me and Seb into filming. It went something like this:

Tim: ‘Do I bother you?’

Neil: ‘Don’t waste yourself.’

Tim: ‘What’s your style?’

Neil: ‘The art of fighting without fighting.’

Tim: ‘Show me some.’

Neil: ‘Don’t you think we need more space? That island. We can take this boat.’

Tim: ‘OK.’

And so on, according to the Enter the Dragon script culminating with one of them jumping overboard resulting in exasperated looks from Ting, Tang and Tong and a backtracking manoeuvre to rescue the man overboard

Another film which was quoted ad nauseam on this trip was, of course, Apocalypse Now, from which we understood that ‘Charlie don’t surf’ and that it was advisable to ‘Never get out of the boat’, never mind the smell of napalm in the morning.

Only a few hours out from Cat Ba we found ourselves in a DWS wonderland of insane karst limestone towers that were all around and contained seemingly unlimitless DWS opportunities. So we amused ourselves on the best-looking crags we encountered such as The Kennel and Saigon Wall, until it was time to anchor up for the night and cook dinner. That evening, in the dark, Tim and I discovered that the phosphorescence scattered off your limbs while swimming gives an amazing lightshow while we circled the nearest rock tower.

Sleeping on deck we were up with the sun the next morning, and after coffee, my need to ‘log out’ became acute. I still hadn’t deciphered from the boatmen where the bathroom was, so I thought, fuck it, and jumped in the sea. I’d never logged out while swimming before, so the length of jobby surprised me. I thought it was some species of poisonous Vietnamese water snake that had surfaced to bite me, resulting in some undignified splashing and swimming to the entertainment of all aboard, especially as there was a bathroom, of sorts, at the back of the boat – basically holes in the deck. The bastards hadn’t told me about them, and at least you didn’t get wet using them.

Tim on Ho Chi Minh. Photo climbderock.

The first crag we came to that day was, for some reason, called The Log Cabin, and then we found the spectacular Archway which gave Neil Ho Chi Minh at F7c and then the amazing Pyramid Cave which gave Ha Long Nights at F7b.

That Ha Long Night, one of us felt the need for some privacy to attend to some urgent personal needs, and so the little wooden rowing boat that was used to ferry us from the main boat to the DWS was henceforth christened ‘the tug boat’.

Grant Farquhar on Ha Long Nights. Photo climbderock.

Now we come to Night Rider. This is not a DWS, it’s a sport climb and must be one of the best F7bs in the world. It is situated on a triangular, vertical wall in Ha Long Bay on an island that, no doubt, has a local name but which we christened ‘Han’s Island’ after, guess what? Enter the Dragon. Anyway, the central orange streak of melting limestone obviously needed to be climbed, so we moored the boat hard up to the limestone shelf at the base of the crag and set to work.

Tim and I trad climbed up the left-hand ridge and then abbed down the centre with drill and bolts. My memory escapes me for who did what, but I remember placing the lower off, about 30m off the deck, and the lower bolts, so Tim is probably responsible for the exponential bolting in the upper section, which can result in a 15m fall if you blow the crux move 1m before the lower off (which I took on my first attempt to lead the route to the disconcertion of the boatmen). But we hadn’t climbed it yet.

Grant Farquhar below Night Rider. Photo climbderock.

That night, there were the usual party shenanigans on the boat, including, bizarrely, a shrine to a Friedrich Nietzsche book that I was reading at the time. I went to sleep. Meanwhile Tim and Neil decided to take the tug boat and go and climb the route – by headtorch in the dark. Both failed to lead it and took the ride, hence the name Night Rider. But the next day, we all led it.

The DWS continued in this vein with venues we found such as Lulworth 2, The Vietwand, Jellyfish Wall, and The Lion’s Den until the boatmen informed us towards sunset on one day that: ‘We can’t stay any longer because of bandits. I’m afraid that we did not take this information seriously, in fact, someone shouted: ‘Don’t Panic! Bandits at 6 o’clock!’ Nevertheless, it was time to head back to Hanoi.

Did we find any surfing? No, apparently, Charlie don’t surf. The horror, the horror.

20 Dec 24: Inaccessible Pinnacles

‘There are steps around the side!’ was a daily quip from passers-by while my friends and I were climbing on the vertical sandstone walls of Dundee University in the 80s (no climbing gyms in those days).

Well, jokes aside, they were right. We all know that rock climbing is a contrived pursuit. You can always walk around the crag to the top, right? Well, you can’t always; some summits cannot be reached by their easiest route without climbing, for example: The Inaccessible Pinnacle, Napes Needle, and The Cioch.

In the UK we have various classifications of peaks: Munros, Corbetts, Grahams, Marilyns, Dodds and Tumps with various different definitions, but what is the hardest-to-reach summit in the UK by its easiest route? I propose a number of candidates below in a rough descending order of difficulty.

The Old Man of Storr. Photo credit isleofskye.com.

1. The Old Man of Storr on Skye

The Old Man of Storr 220ft, Very Severe. First ascent 18th July 1955 by Don Whillans, J Barber and GJ Sutton. Start at the end of the Pinnacle facing the Storr Rock. Facing the Old Man, start just to the left of the corner on your right. A long time was occupied in scouting around before finding the route, and Sutton went up 20ft or so at the other end of the Pinnacle (facing Portree) without finding it possible to continue. It might be possible to make other routes, but given the quality of the rock, they would probably be both difficult and dangerous. The Storr Rock also seemed to offer possibilities, but as the summit of the Old Man was reached at 8pm, they were not investigated. Go up about 20ft to a circular hole in the rock. A piton is inserted but is useless, affording only doubtful protection. Then traverse left (the crux, both strenuous and extremely severe) to gain the top of a prominent nose in the centre of the face. Climb to a grassy cave directly above, then left again to a ledge of shattered blocks on the left edge of the pinnacle (70 ft) The rest is easy. Move right above cave and continue diagonally for about 100ft. Climb a corner chimney and then leftwards to the top, quite exposed and small , where a cairn was left with a couple of coins under it. The descent was made by two rappels, the first to the block ledge. For this, at least 200ft of rope is desirable. Whillans led the climb. (Accounts by both Whillans and Sutton received).

SMC Journal

You get a good view of this pinnacle in the opening sequence of The Wicker Man – if you haven’t watched this gem then I highly recommend it. The original Whillans route, described above, used a peg for aid. It was given the infamous ‘Scottish VS’ grade and now gets E5. I failed to climb it in the 80s when the start appeared to be a protectionless overhanging groove on shit rock. I was suitably humbled and further impressed by the exploits of ‘The Don’.

The Portree Face of the Old Man was climbed by G Lee and P Thomson in September 1967, again at ‘Scottish VS’, and is now graded E4. Mick Fowler and Jon Lincoln did the first ascent of the Staffin Face in June 88 as Jon reports: ‘We were actually there to do Original Route and failed to find it through incompetent guidebook reading. I’m glad Mick lead it as I wouldn’t have gone near it. It’s the only rock I’ve climbed on that I could crush in my hand. I particularly remember a belay on a very collapsing thread. It was definitely a case of if Mick falls off, hope his gear is good as the belay probably won’t hold. It was the end of a great week including the first ascent of Big John.’

Further repeats include Dave Macleod on the Staffin Face: ‘More or less every hold was freely detachable’, and Leo Houlding (in 2004) on the Portree Face: ‘I thought I was going to die… At 5c it logically equates to E4, but it felt more like E7’. None of the Old Man of Storr routes are graded less than E4 in the current guidebook.

The Dodds are defined as ‘hills between 500 and 600m high’. The Old Man of Storr qualifies as a Dodd, making that list extremely difficult to complete, and apparently, no one has done it yet.

So, the Isle of Skye not only contains the hardest-to-reach Munro summit (the Inn Pinn) in the UK, but also the hardest-to-reach rock climbing summit in the UK (The Old Man of Storr). I also seem to remember that Skye had Britain’s ‘last unclimbed green summit’ in the UK which was climbed by the late, great Chris Dale on the Quiraing.

2. Staffin Chimney Stack on Skye

This slim pinnacle is found just north of Kilt Rock (again on Skye). There are two routes to the summit: Over the Rainbow climbed by Bill Birkett and Bob Wightman, and Sheer Sear climbed by Gary Latter. Both are E5, but the good gear and quality of the rock plus the close proximity to the main cliff and the bolts on top make this – in my eyes – an easier summit to conquer than Storr.

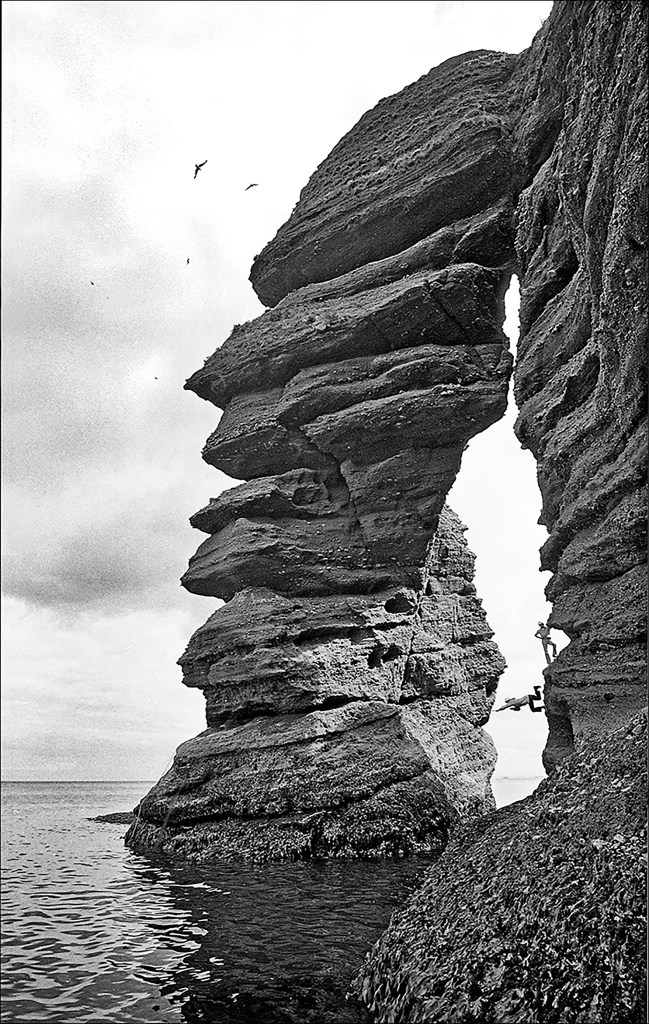

3. The Orval Pinnacle on Rum

The Orval Pinnacle. Photo climbderock.

The summit of this improbable pinnacle was first reached by Dave Bathgate and Hamish MacInnes by Tyrolean traverse in 1977. The first climbing ascent was made by Graham Little in 1984, and I made the second ascent in the late-80s. The Orval Pinnacle might be a Tump according to the official definition: ‘Tumps are defined as British Hills with more than 30 metres of prominence.’ If so, this summit will prove a major obstacle to Tump-baggers, unless they can climb loose and serious E3 5b.

Grant Farquhar on the summit of the Orval Pinnacle during the second ascent. Photo climbderock.

4. The Parson in Devon

The Parson by John Cleare.

The Parson is visible from the train on the section of track between Dawlish and Teignmouth and the approach is through one of the train tunnels. It’s one of the ‘esoteric’ stacks in Ladram Bay, such as Big Picket (which may be harder at XS 6a) and other horror shows. The Parson was climbed by Keith Darbyshire, Peter Biven, Johnny Fowler, and S Nicholls in 1971 and is about 3 pitches of E3 5b (although it gets E4 in the new South Devon guide) including the infamous ‘Brown Spider’ pitch.

5. Old Harry in Dorset

Old Harry by John Cleare.

This 25m chalk sea-stack was first ascended via a combination of free, ice and aid techniques up the west face by Simon Ballantine and J Henderson in 1986. The second (and first free ascent) came from Mick Fowler, Chris Newcombe, Mark Lynden and Andy Meyers the following year up the east face at XS 5c although Fowler described this as ‘High Rocks 5c’ which, for people unfamiliar with south-east sandstone climbing, means more like 6a.

6. The Needle on Hoy

There are some cliffs south of Rackwick Bay with this 55m stack at their southern tip. The first ascent was made by Mick Fowler, Steve Sustad and Nikki Dugan in 1990. On the first ascent, access involved removing clothes and abseiling 61m directly into the sea in the geo, followed by a swim across to ledges on the far side. The three-pitch route is graded XS 5c.

7. Lovers’ Leap Rock in Ireland

There is a 50m stack at the tip of Loop Head which forms the north side of the Shannon Estuary. It is called Diarmuid and Gráinne’s Rock or alternatively Oileán na Léime (Lovers’ Leap) and has a flat dome-shaped grassy top. The first ascent at XS 5c by Mick Fowler and Steve Sustad in 1991 involved abseiling from the car bumper into the deep, narrow channel separating the stack from the main cliff and swimming across to sea-level platforms at the base of the stack.

8. The Drongs in Shetland

The Drongs are a well-known and spectacular series of 30m stacks off the Ness of Hillswick. The Main Drong and Slender Drong were climbed in 1982 by Joe Brown, Don Whillans and Kenny Spence at XS 5b. The rock is friable and quite broken. They lie 1km offshore with water depths of over 70m nearby, so they are approached by boat if weather and sea-state permits.

9. The Old Man of Hoy

The easiest route up the well-known Old Man is graded E1 5b.

10. St Kilda sea-stacks

Stac Biorach by Marc Calhoun.

The hardest-to-reach summit in this remote archipelago is probably that of the 73m Stac Biorach via ‘The Thumb’, which is only Severe but was climbed by the St Kildans as early as the 17th century as observed by Martin Martin on a visit in 1697. It’s no wonder that Robert Moray wrote in 1678 that ‘The Men seldom grow old; and seldom was it ever known, that any man died in his bed there, but was either drowned or broke his neck’. St Kilda also possesses the highest stack in the British Isles in the shape of Stac an Armin. Read more about the St Kildan climbers and The Thumb in my book The Blue Cliff.

9 June 24: Agrippa

I don’t have any pics of that day on Carn Dearg Buttress so here is one of me on Uncertain Emotions in Glen Coe. Photo climbderock.

‘Ben Nevis’ is an Anglicisation of the Gaelic ‘Beinn Nibheis’. There are a number of theories as to the origin of Nibheis, with perhaps the best explanation being that it derives from beinn nèamh-bhathais: ‘the mountain with its head in the clouds’, or ‘mountain of heaven’.

Justly famed for its classic ridges, the Ben had relatively few high-standard modern routes in the 80s and 90s with the venue for these being on the magnificent Carn Dearg Buttress. I frequently hitch-hiked from Dundee through to Lochaber to climb in the Coe or on the Ben, but I didn’t climb on Carn Dearg until 1992 when I drove up from North Wales for the weekend to meet Rick ‘The Stick’ Campbell and Paul ‘Stork’ Thorburn in Fort William.

It was a scorching blue sky day in June as we trudged up the Allt a’ Mhuilinn. Approaching the buttress it was clear that other teams were heading for the same objective: Mark ‘Dr Death’ Garthwaite and Davie ‘Cardboard Box’ Greig formed one team with Murray and Carol Hamilton the other. We were all heading for Agrippa. There was a severe traffic jam as we all arrived at the bottom at the same time, but Garth and Davie had won the foot-race and so started up the first pitch of Agrippa.

We climbed the first pitch of Titan’s Wall and then decided to do the Banana Groove as a warm up. I led leftwards around the arête along the Patey traverse and then continued up the banana-shaped groove. With my friends belayed around the corner it felt like a lonely lead. The rock was slightly dirty and the holds downward sloping. It kept on coming with lots of great moves, good protection, and then a hard-ish section at the top.

By the time we had all topped out, Carol was getting ready to second Murray on Agrippa, and by the time we had abbed back to the belay ledge she was well on her way up the crux pitch. Meanwhile, Davie and Garth were struggling to find good protection after the first few moves off the belay. While they dithered we did Titan’s Wall which was quickly led by Rick. When I got to the top Carol was getting ready to abseil. I clipped a rusty, old peg on the belay. ‘Murray put that in,’ she said. ‘Thanks!’ I replied.

Back down at the belay we regrouped for the meat of Agrippa. Stork had a go but quickly came down. He had been very quiet all day and it was only later that he disclosed that he was, in fact, severely hungover, so the sharp ends were passed to me. Climbing above the ledge, I got in a crap wire and then pressed on up and right. Unrelaxed, cramped moves lead up to the ‘detached block’ feature on the arête. The climbing was then pretty steady until moves left at the top of the arête led to the finishing ‘slab’ which was a battle against rope-drag to the belay.

We were planning on climbing at Creag a’Bhancair the next day so drove down to the Kingshouse Hotel. Walking into the bar I was greeted by the late, great Paul Williams who, ever-enthusiastic, congratulated us on our ascent of Agrippa.

6 April 24: The Scoop

Strone Ulladale. Photo climbderock.

I was sitting in Pete’s Eats in Llanberis, in 1987, with Paul Pritchard and Johnny Dawes and they were talking about a potential free ascent of Doug Scott’s aid route on Strone Ulladale on Harris.

‘There’s a loose block on it the size of this cafe,’ said Paul.

‘You are Scottish, you could be our interpreter,’ said Johnny.

I considered it, but I had to be back in Dundee the next week for my second year at medical school. So, I bailed on them and hitchhiked from North Wales back to Dundee.

Meanwhile, they headed north from Llanberis, which was a major journey in those days. I think they told me a story, later, about some major epic en route. Anyway, they made the first free ascent which was a major achievement.

I didn’t get on the route until 1996, when I was there with Rick Campbell, Gary Latter and Nick Clements. There was only one good day of reasonable weather forecast in the whole week. We climbed on the superb Lewis sea cliffs and then walked into the big Strone.

Grant Farquhar on the first pitch of The Scoop. Photo climbderock.

Rick had been on The Scoop before and kept on talking about a desperate move on the first pitch that had stopped him before. Belaying me, he was delighted when I went up and sloppily slapped my way through this section and then continued past the belay to run the first two pitches together.

Rick pulling on to the belay ledge above the flying groove. Photo climbderock.

A couple of E4 pitches led to the base of the legendary ‘flying groove’. This is the free version, put up by Johnny and Paul, that bypasses the loose block the size of a cafe. This pitch is well-protected and very spectacular, about F7b+, and the crux of the route. I led it and then some more reasonable pitches led to the final pitch – which is a sting in the tail.

This final hard pitch is probably E6 6a. You have to make a long traverse right from the belay, with no gear, and then contemplate climbing a severely overhanging wall. Once committed on this, there is no going back – you either do it and summit, or take a massive fall and have a complicated bail. On this pitch when Johnny fell off one of the ropes cut on the edge of the ledge.

Grant Farquhar on the final hard pitch. Photo climbderock.

I started up the wall and at one point had to grab the wrist of one hand with the other to pull up on the next hold. I could see an in situ wire above and clipped it, but once I got me eyes level with it I could see that it was a very poorly placed RP that would be unlikely to hold a fall. Never mind, I continued. Thankfully the pissing rain, which we had been sheltered from en route by the massive overhand had stopped and Rick led the last pitch to the summit in the sunshine.

13/3/24: The first F8a in Scotland

I first went to Balmashanner Quarry with local Angus guru Neil Shepherd. A dentist by trade he spent his work days drilling holes in teeth and his leisure time drilling holes in crags, as exemplified by his route: Driller Killer. At the time there were no routes in the shanner and as we abseiled down Neil remarked that some of the hardest climbed in Scotland could be produced there (he was right).

Neil Shepherd the Driller Killer, in 1988, cleaning what was to become Manifestations, F7b, at Balmashanner by Dave Douglas.

Not looking at it with the bolter’s eye, I just saw sheer unprotected steepness and was not particularly keen to get involved. In contrast, Neil was enthused and started developing the crag with Dave Douglas. The duo produced a number of excellent routes and after repeating them their enthusiasm infected me.

Neil had bolted a project on the right-hand side of the wall which had a number of bolts and then a peg. I dogged up the bolts and then clipped the peg. Climbing above this I shouted, ‘Take!’, and lobbed off onto the peg which promptly came out resulting in a rather large fall. ‘Shit! That was just a cleaning peg.’ Neil told me later after I relayed this story to him. He later completed the bolting, and the route sat there as an unfinished project.

It felt like the pressure was on as Stuart Cameron and I drove up the Forfar Road in my Renault 5 in 1991 to attempt the project which was to become Gravity’s Rainbow. Fortunately I did it first redpoint and then Stuart did it immediately after. We owe Neil an apology for stealing his route.

I see that Gravity’s Rainbow has been upgraded in the guidebooks and on UKclimbing.com from F7c+ to F8a. We actually graded it F8a at the time, but the grade subsequently dropped to F7c+ until the recent upgrade.

This got me thinking about what route was the first of that grade (F8a) in Scotland. In the early-90s sport climbing was relatively new to Scotland. Aid bolts had existed for many years and Cubby had utilised some of these during his first ascent of Fall Out on Upper Cave in 1982. Some quarries were bolted, such as Legaston Quarry, and the odd bolt had appeared elsewhere.

Outside the quarries sport climbs first appeared in 1986 on Upper Cave with Cubby’s Marlina, F7c, and the Tunnel Wall with Cubby’s Uncertain Emotions, F7b, and the Brat’s Fated Path, F7c+. Bolting, especially on mountain crags, was, of, course, controversial with the Tunnel Wall route names reflecting this.

Sport climbing development then expanded to other areas such as other Dunkeld crags, Glen Ogle and Dumbarton with Duncan McCallum’s Spiral Tribe, F8a, at the former and Andy Gallagher’s Sufferance at the latter, both in 1993. Steall Hut Crag in Glen Nevis was another early sport venue.

So, unless I’m missing a route somewhere, Gravity’s Rainbow, climbed in 1991 appears to be the first sport climb in Scotland of the grade of F8a. This is something I find amusing as at the time I was very much a trad climber and didn’t do much sport climbing, especially in Scotland. I had a dream, never to be realised, of climbing Fated Path without the bolts and then removing them to make into a trad route, kind of like Scotland’s Indian Face.

Of course Cubby’s Requiem, climbed in 1983 and a candidate for the hardest route in the world at the time, blows all these routes out of the water being F8a and E8 on trad gear, but I guess it’s not a sport route!

3 Feb 24: Don Quixote and Spanish slang words for perineum

At this time of year in Bermuda it’s a pleasant temperature for me to walk into and out of work, which takes about 30 minutes from our house in Hungry Bay to Hamilton. I’ve been listening to a lot of Blindboy podcasts during my journeys with my favourites, so far, being the ones about Greek mythology, Simulation Theory and Irish lifting stones. I’ve also been climbing a bit at Tsunami Wall and still being crippled from post-Covid flare-up of Psoriatic Arthritis I decided to climb the wall right of Davie’s route, La Cucaracha. This provided two, low-grade, logical routes, as described below, with my ascent of La Mancha occurring today.

Ben Kaplan and Jackson Chin on La Cucaracha. Photo Climbderock.

I put the bolts in during my afternoon off work last week and was anticipating climbing it today, but the weather forecast was bad. I was busy all morning with kids and the nanny was due to arrive at midday. The Scotland vs Wales 6 Nations match was due to start at 1pm and the weather forecast was bad with 10-20 knots west wind and bands of showers forecast. So, I had a major juggling match on my hands.

At 11:30 I could see a band of showers approaching Bermuda from the west on the weather radar, but thought I could beat it. So, with climbing bag packed, I stood sentry at the front door awaiting the arrival of the nanny. She arrived, and with a brief handover, like an F1 pitstop, I was off racing to the crag. I never eat breakfast and, according to Gordon Gecko, lunch is for wimps anyway.

The road was wet, and it was obviously pissing down to the north but I carried on. The ground at the top of the crag was slippy and wet but I could see that the route was in climbable condition so I quickly rigged the ab rope and got on with it.

Arriving at the base, I rigged my ground anchor, lead-rope-solo Grigri and back up knots and prepared to set off. At that moment the heavy spots of rain turned into a full-in cloudburst. When this happens in Bermuda, it feels like someone has pointed a fire-hose at you. I untied from the system and scurried off to hide in the bowels of the cave but not before getting completely soaked while wearing T-shirt, rockshoes, chalkbag etc.

Fortunately, after 15 minutes the shower passed and the rain stopped. The wall, being fairly steep, was still pretty much dry except for the start and the finish. I, however, was drenched. No time to waste, though, the rugby would be starting soon.

Steady moves led past the first and second bolts to a good hold on La Cucaracha from where I could clip the final bolt. At this point, the footholds are smears and my wet shoes kept rolling off. So I felt too pumped to make the final moves and fell off onto the bolt and lowered off.

After sorting out the system for my next go and an extra five minute wait I climbed through to the wet top-out, just as it started to piss down again. I made it back in time for the second half which was a tense affair with Scotland beating Wales 27-26.

JIM PERRINEUM 5.10b 12m

The right-hand line in the vertical wall below the large skylight. Scribble past four bolts to a full stop at belay above. Grant Farquhar & Jackson Chin 24/1/24.

LA MANCHA 5.10a 12m

If this route was a Blindboy Podcast it would be entitled: Don Quixote and Spanish slang words for perineum. The left-hand line in the vertical wall below the large skylight. Clip the first bolt of Jim Perrineum and climb up and left past another bolt to join La Cucaracha at its final bolt. Grant Farquhar Lead Rope Solo 3/Feb/24.

28/1/24: Lady Charlotte

Lady Charlotte’s Cave in Perthshire can be found near the Dunkeld Cave Crags. It is a grotto that was artificially enhanced by John Murray, 3rd Duke of Atholl (1729–1774) for the pleasure of his wife Lady Charlotte Murray (1735–1805). One of their nine children was also called Lady Charlotte (1754–1808) but it was the mother, rather than the daughter, whose name was given to the cave. There is a story in one of the climbing guidebooks of a somewhat salacious nature relating to Lady Charlotte’s activities in the cave but I could find no evidence for this story when researching this blogpost. One tale that is interesting, though, is that her husband, the Duke, died at the age of 45 years from drowning in the River Tay in a ‘fit of madness’ after drinking a cup of Hartshorn (Hart’s Horns were the main source of ammonia in the 17th century).

A climber (can’t remember his name) on Lady Charlotte in the 80s. Photo climbderock.

Cubby’s route Lady Charlotte, climbed in 1980, on Upper Cave Crag was one of the first E5s in Scotland and remains one of the best. It’s an amazing route, a bit like the Right Wall of Scotland. I first did Lady Charlotte in the 80s. Since then, I’ve lead it numerous times: I went to Upper Cave a lot. But, one day while I was working on Marlina I decided to have a lap on Lady Charlotte at the end of the day. I seriously underestimated the route through previous experience and nearly fucking died. On this particular occasion, I got through the initial section past the RPs and suddenly was on a terminal pump. In the scoop above, I stuffed the 1-and-a-half friend into the slot out right, but it wasn’t in correctly, and I was looking at a ground fall. I wobbled through the moves to the Pied Piper. Now, at the age of 56, I would have said fuck this! And lowered off at that point. But, back in the 80s, as a spunk-fuelled 20-something with pride and 20’s strength I kept going to the top.

23/11/23: The Farquhar brothers

When I first started climbing I found my name in the Craig a Barns guidebook: ‘G Farquhar’. He was frequently climbing with ‘R Farquhar’ who I understand was his brother. I’ve always been intrigued by the mysterious climbing Farquhar brothers – who are probably my cousins – but I’ve never been able to find out more about them. Whilst looking fruitlessly through the SMC Journals for the first ascent date of Baillie’s Overhang, I found the route described below in the 1968 journal.

SMCJ, 1968.

It’s not every day that you come across an unclimbed route on the crowded Upper Cave Crag (which I know well). To my knowledge, no one has free climbed this route. Yes, every bit of it has been free climbed, but I doubt if anyone has made a continuous ascent. The free version would be: Pied Piper to Ratcatcher followed by Necrophilia to Morbidezza. Reverse Morbidezza to Rat Race, then reverse the diagonal crack of Marlene and follow Fall Out Direct to the belay of that. Traverse across Corpse to Coffin Corner then finish up ‘Coffin Arete’. I would have to do some more research to find out what route is now taken by ‘Coffin Arete’ but the most likely candidate is High Performance. So, the entire route should go at a grade of E5 5c, 6a, 6b, 5b, 6a.

18/11/23: Arrochar

I wish I was a fisherman

Tumblin’ on the seas

Far away from dry land

And it’s bitter memories.

Fisherman’s Blues. Mike Scott.

This was the song blasting out from Gary Latter’s stereo off Byres Road in Glasgow that he was using as a weapon to get me and Mark (Face) McGowan, dossing on the floor, awake. The Edge of Extinction was our goal that day. Face and I had already climbed the first pitch, but an onslaught of pissing rain defeated our plans to climb the second pitch. As I looked up at the pitch from the belay before abseiling off I remarked that it looked about Severe – this is probably the most deceptively easy-looking E6 pitch that I have ever seen.

On our next go, that day, I was freezing belaying Gary and not ready to climb but when I touched the rock an electric current went through me. It’s hard to explain but I was suddenly climbing extremely well, and confidently, and nothing was going to defeat me.

Grant Farquhar leading the second pitch of The Edge of Extinction, E6 6a,6a. Photo Steven Yates.

The Edge of Extinction is on an obscure Arrochar crag called The Brack that faces The Cobbler AKA Ben Arthur across the glen. The Cobbler is definitely one of the most interesting rock climbing venues in Scotland. Close to the bonny bonny banks of Loch Lomond and therefore close to Glasgow it has a long history with Glaswegian climbers.

The Cobbler route that I was most interested in was Cubby’s Wild Country. In 1979 he seemed to have no idea how hard he was climbing – giving this route a grade of E4 6b. Since then, it has had probably only had a few repeats, despite featuring in Extreme Rock, and is now regarded to be E7 6b which makes it possibly the first E7 In the UK.

I went there a few times. Once with Mark McGowan where we were planning to bivi at the foot of the crag. We got up there late on the Friday night, and it was looking like it might piss down at any moment. Face had his sights on a Dave Griffiths route called Rest in Pieces that ludicrously finished at a lower off from a wire. He quickly abbed down to check it out then tied on for the lead. The mist and clag was already setting in but he climbed past the wire at the top of the initial crack and onwards to the top to produce Rise to the Occasion, E5 6a. It was just as well that he sent the route, first go, because the rain continued to piss down and we had to bail the next day.

I was there when Rick Campbell made the second ascent of Cubby’s E5, Ruskoline, describing the dirty rock as: ‘Pure fucking David Bellamy’ en route. Osiris was another Dave Griffiths route that I made the third ascent of, belayed by Kev Howett who had done the second ascent – another great route.

In 1989, I attempted to free climb Baillie’s Overhang with Gary Latter. My onsight attempt finished at, what is now, the final section of Gary’s route Dalriada; it was only about E3 5c to there. I free climbed the lower section of Baillie’s Overhang to get to the ledge and then escaped up Wither Wether after failing to make progress on that final overhang. It didn’t occur to me at the time, as I regarded it as a failed attempt to free Baillie’s Overhang, but looking back I guess that was probably a first ascent. I abbed down to try and find some protection, finding an obvious placement for a large angle peg (that I didn’t have). I tried again anyway but couldn’t commit to that final, hard, section without gear. It wasn’t too dirty, it was the lack of protection that stopped me on that final section of Dalriada – without pegs I had nothing to protect the moves off the ledge. Gary went back and climbed, what is now, Dalriada with an independent start to complete what is probably the most photogenic route in Scotland.

1970 SMC Arrochar guidebook.

The last time I was there was the early 90s. My girlfriend at the time and I had been climbing in the north of Scotland for a week and I wanted to stop in Arrochar on the way back to North Wales to do Wild Country. I was climbing very well at the time – onsighting E6 easily and a lot of E7s – so it was within my comfort zone.

As we pulled into Arrochar, in my white Vauxhall Cavalier SRi, two things happened. First, I could see the sun setting over The Cobbler and the orange sky revealed no clouds meaning good weather. Second, the timing belt on the car chose that moment to snap. Needing to be at work on the Monday meant I spent the Sunday organising car breakdown rescue rather than climbing Wild Country.

If I was in that position, now, I would have fucked the car, fucked work and climbed (or failed on) Wild Country regardless.

3 Nov 23: Sundance

The South Face of Cerro Trinidad. Photo Grant Farquhar.

Beware the Ides of March.

Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare

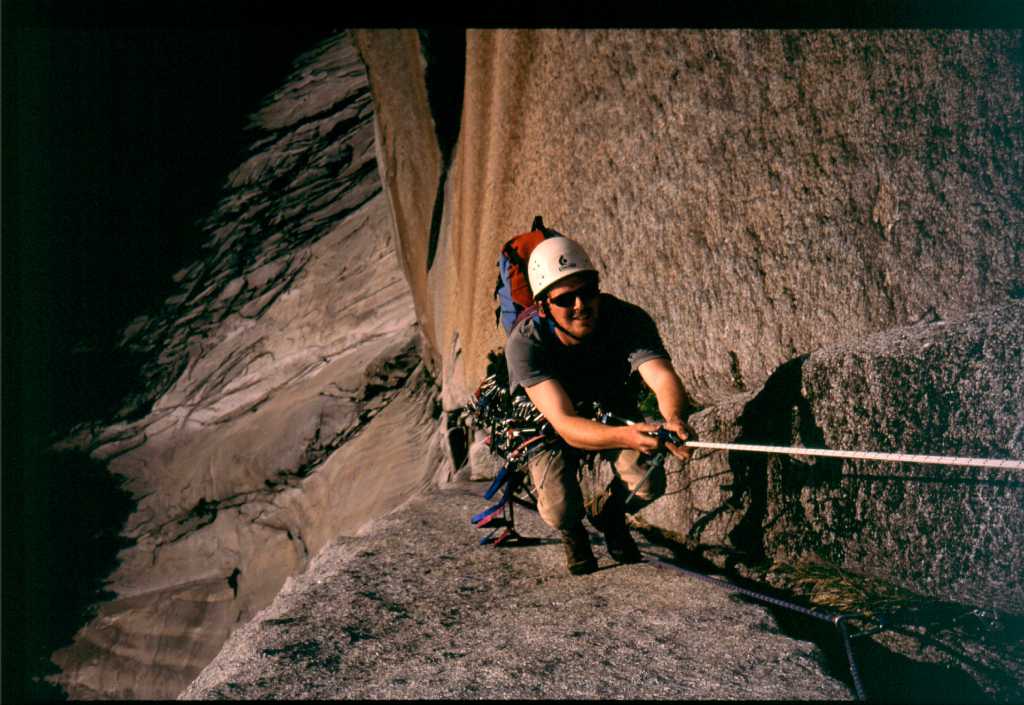

It was 25 years ago: the ides of March 1998. I was in Cochamo with the strong British climbing team of Crispin Waddy, Noel Craine, Dave Kendall and Simon Nadin. The climbing potential of this valley in the Patagonian Lake District had been discovered the year before by Crispin who recruited Noel to try and climb the obvious challenge of the South Face of Cerro Trinidad which due to a number of factors – not least forest fires – they failed to get up. So, the following year, we were there to finish the job.

The trip out did not go smoothly. In retrospect flying KLM was a bad move, for two reasons: i) they lost our bags and ii) we lost our sanity – the (delayed) transfer via Schipol gave us several hours to ‘investigate’ the Amsterdam coffee shops and their various wares. Due to this and other factors we ended up on different flights out of Schipol with me on a flight to Ecuador (instead of Santiago) intending to rendezvous with the others at Puerto Montt, which I eventually did.

Back in ’98, Cochamo was not the well-established climbing destination that it is now. In fact zero routes had been climbed at that point. The walk-in to the climbing area takes a day up the river valley above the town. The next day we macheted our way through the jungle to the base of the wall and established base camp at the foot of the wall.

The next morning I awoke and opened the tent door. Lazily I watched, what I initially thought were, some large bumble bees harvesting pollen from the wildflowers. After a few seconds I realised that they weren’t bumble bees – they were tiny hummingbirds.

The book I’d brought was Ulysses by James Joyce. I’ve tried, and failed, to read that book at least three times in my life. I eventually deposited it in the hollow trunk of a dead tree at the base of the wall.

More loads needed to be carried and while the others did that, Crispin and I set off climbing the initial five pitches up a pillar at the base of the wall and fixed ropes on this. From the top of this, Crispin, Noel and Dave’s route would go left while Simon and I would be going right.

From the top of the pillar, Simon led a completely free, and hard, E5 6b pitch to gain a small belay ledge. I followed and was then faced with the choice of an offwidth crack to the left or a thin seam directly above. I opted for the seam but free climbing was quickly shut down and I continued on pegs and beaks for a bit until I fell off and badly sprained my ankle clipping the belay ledge as I fell past it.

We went down. That night my ankle swelled up and I had doubts about being able to continue the next day. I didn’t share my doubts, though, and thankfully found that I could walk on it the next morning. We jumared up the ropes and I commenced battle with the offwidth which took me several hours. I continued past a ledge, where I should have belayed, and ended up on a hanging belay higher up after running out of gear. Annoyingly it transpired that I could have missed the offwidth out by traversing right from the lower stance to a crack that led back left. I was aware that Simon, being a world champion competition climber could probably have pissed up the offwidth in a fraction of the time I took to thrutch my way up it. But, he didn’t say anything and led through.

We continued in that vein, aid climbing up overhanging cracks that were choked with mud and vegetation until we reached a fantastic ledge that two people could lie down on, end to end. We decided that we would bivi here and go for the top in a day.

Simon Nadin on Sundance. Photo Grant Farquhar.

So, the next day, we rested and then towards evening jumared up with our bivi gear. It was a palatial ledge and the sunset was flaming and spectacular. The others had also decided to bivvy on a ledge on their route

The next morning, at first light, I was surprised to observe activity at the foot of the crag. ‘There are people at the base,’ I said to Simon. It later transpired that ‘the people at the base’ were Crispin, Noel and Dave who had become concerned about the weather and abbed down during the night while Simon and I snored on obliviously.

We carried on through roofs and laybacks to reach the summit in the early afternoon – the first ascent of the wall. The descent involved a couple of abseils and then a boulder-choked gully which, with a heavy haulsack on my back, turned my legs into rubber.

We eventually made base camp and the following day, whilst the others completed their route, we went on an extended trip with American climbers Steve Quinlan and Nathan Martin who had just completed their route – Welcome to the Jungle.

Walking out, the next day, our first stop was in the first shop we came to in Cochamo for beer and fags. Then we went surfing at Pichelimu.

Years later, in the Cheddar Gorge, one rainy climbing day, I had a conversation with Alex Honnold about our route in Cochamo, Sundance. Turns out that he’d been on the route. ‘It’s the only steep wall in the place,’ he said. Which, I guess, is true.

25/6/23: The Highlander

Grant Farquhar on The Highlander. Photo climbderock.

There Can Be Only One by Grant Farquhar

In 1988, I was a neuropharmacology lab rat, experimenting on real rats; removing their brains to analyse their hippocampi. It was a serious business, especially for the rodents. I was also a crag rat and sometimes it seemed like a good idea to remove one’s brain on a serious trad route.

By the 8th June, exams and university was over for the year and a long summer of nothing but climbing stretched out in front of me. For a change, in Scotland that year, the weather was a kind of magic run of sunny days, and I was heading out west to take advantage of it. I was supposed to rendezvous with another climber, Dave Griffiths, in Fort William at 5pm that day, but the hitchhitching along the Crieff road was tortuously slow.

By 8pm, I’d been standing in this one spot in Glencoe Village in the gloaming for a while and was pretty sick of it. Opposite me was a row of cottages. A Ford Capri pulled up, and out stepped a thin figure with longish dark hair and a droopy moustache. He had the kind of classic hunchback climbers posture – common in the 80s – that was cultivated by too much spent time spent on fingery, vertical walls and no knowledge of antagonist training. As he disappeared into a static caravan I thought: I wonder if that’s Kev Howett? I’d seen his picture in various climbing books and magazines as one of the ‘Glen Nevis cruisers’. I decided to pay him a visit.

I introduced myself and so started an instant and life-long friendship. I ended up staying and climbing with Kev for the next few days, mainly in Glen Nevis and Gars Bhienn where I got fried alive making the third ascent of Pete Whillance’s White Hope.

But I had my sights firmly fixed on somewhere else. Like most men I’ve always been fascinated by breasts, but the Cioch is something else. A plinth, fit for a king, halfway up a massive rock face in a massive amphitheatre in the Cuillin of Skye. The shadow cast by the projecting pinnacle onto the neighbouring slab resembles a breast, or ‘Cioch’ in Scottish Gaelic. I had climbed there over the preceding few years and couldn’t help but notice the absolutely gobsmacking line of the overhanging arete on the front of the Cioch that was to become The Highlander.

So, a few days later, Gary Latter and I went to Skye, making a bee-line for Sron na Ciche and the Cioch. Impatient, I started up the arete on-sight. Bold moves of about 5c led to a ledge with a good cam placement just below the top. Above, the arete bulged out before rounding off into a steep slab. The final moves involved swinging left around the arete on a good hold and reaching up for the very slopey slab above. Try as I might, I couldn’t figure out this section. Disappointed, we did the Overhanging Crack variation – very good and E2 – before going down to the BMC hut in Glen Brittle.

The next day I still couldn’t make the crucial last move, even getting both hands over the top before falling off. I had a sideways RP 2 which pulled out and I stripped the sheath from Gary’s rope in the swinging fall around the arete onto the cam. I was pretty pissed off by then and admitted defeat. Gary had abseiled the route and thought that he could do it. I gave him my blessing and held the ropes. But even utilising his secret weapon, Friars Balsam, on his fingertips, he didn’t manage it either.

We exchanged some F-words with ‘Effing George’ Szuca and Colin Moody, who were making the first ascent of Strappado Direct, and climbed some more in the perfect evening – including the third ascent of Cubby’s E5 Zephyr – before realising the time was so late. It was 19:55 and the last ferry was at 21:00. The following day was a Sunday: no ferry service.

We ran down to the car (which we had to jump start) and then drove at warp speed to Kyleakin. We nearly chopped a cat and numerous kamikaze sheep but we made it, just. ‘I think you lost your trailer,’ observed the ferry man wryly as we roared onto the ferry.

The following year, 1989, I was keen to get to grips with the route again. A photo had appeared of me on the route in High magazine with the caption: ‘Grant Farquhar attempting an unclimbed arete, somewhere on Skye.’ So I was slightly paranoid that someone else would beat me to it.

I spent Easter, traditionally, in Pembroke and then hitched to North Wales. I did loads of routes and climbed my first E7, Raped by Affection, so was climbing reasonably well. Returning to Scotland, on Tuesday 18th April Gary and I did Marlene at Upper Cave crag and two days later we drove to Skye. The mountains still felt wintry; it was cold and conditions were perfect. This time I decided to abseil the route first to check out the gear and those devious moves onto the final slab. This time I kept my head on my first go on the lead and the immortal Highlander was born.

21/2/23: Drapetomania

Spittal Pond bouldering. Photo: Climbderock.

I have been bouldering at Spittal Pond which was an area developed by Timothy Claude. There is a lot of rock here but not much of it hangs together as making worthwhile problems. It’s still a cool place to visit and climb though. I knew Jeffrey’s Cave, a stop on the African Diaspora Heritage Trail was in Spittal Pond somewhere and that it was hard to find. So it proved: I couldn’t find it. Which is why, I guess, Jeffrey – a runaway slave – successfully hid out in it for a month. But one day after wandering back from a boulder cave that I, mistakenly, thought might be Jeffrey’s Cave I found the real deal. This cave is so well hidden that I couldn’t immediately find it the next time.

Looking into Jeffrey’s Cave. Photo: Climbderock.

Sitting in the cave I tried to picture myself as the legendary Jeffrey. Sure there is a nicely framed view of the turquoise water, but the front of the cave is open to any south wind and the floor, being made of rock, was hard and would probably not make for a comfortable night’s sleep. I was, literally, sitting in his position but I was in reality a million miles away. Here was I: a free, privileged white male, investigating the cliffs and caves for rock climbing potential whereas Jeffrey would have been born into chattel slavery and faced a life of brutal work and threat of punishment. I don’t think he would have been eyeing up the cracks in the ceiling of the cave as potential challenges for the frivolous pursuit of rock climbing. I decided to find more about Jeffrey.

The earliest source I could find for this story was in the Royal Gazette in 1923 where it was recounted under ‘Tales and Traditions of Old Bermuda’ by Winslow Manley Bell. It tells how ‘a negro named Jeffrey’, of Smith’s Tribe (Smith’s is the parish that Spittal Pond is in) ran away and could not be found despite extensive searching. It was supposed that he had escaped by ship.

Looking out of Jeffrey’s Cave. Photo: Climbderock.

The story goes on to describe how, after about a month of Jeffrey’s absence, ‘the master of the plantation’ observed, one day, the 15-year-old mulatto girl who served in his kitchen slipping away at nightfall with a package towards the south shore. He presumed that Jeffrey was lurking somewhere nearby and that she was bringing him food. After ‘a long and tedious search’ the next day he discovered Jeffrey sleeping in his eponymous cave. The story does not give a date for the story or recount the fate of the unfortunate Jeffrey.

In 1616, chattel slavery was already in use in Bermuda. By decree of Governor Henry Woodhouse’s Council it became law in 1626 and continued throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries until emancipation on 1 Aug 1834 when the act to abolish slavery was passed in Great Britain. In Bermuda, the annual Cup Match public two-day holiday still marks this historic event.

One of the sources that I was able to use to research Jeffrey was the Bermuda slave registers. In 1819, the British Government formally asked all territories of the British Empire to prepare such registers. Bermuda submitted three slave registers and the second and third from 1821 and 1834 are available online via the Bermuda College website. The 1834 slave register (which listed 1,858 males and 2,319 females, totalling 4,277 slaves) lists ‘Jeffry’ owned by Mary Ball and ‘Geoffry’ owned by Benjamin Patty. There is also listed ‘Geoffrey’ owned by Samuel Trott of Verdmont, but he was five years old in 1833, so we can exclude him as a candidate for the Spittal Pond Jeffrey.

Assuming the name Jeffrey is correct, we have two candidates for the elusive Jeffrey. According to the slave registers, Mary Ball of Smiths owned three male slaves (including ‘Jeffry’) and Benjamin Patty of Pembroke owned two males, ‘Geoffry’ and Syke; and two females, Clary and Nancy. According to information gleaned from the Royal Gazette, Patty’s land was in North Pembroke near the Parsonage so while he had female slaves that fits with the 1923 story, his land being quite far away from Spittal Pond does not fit (Google Maps quotes one hour and 14 minutes as the time taken for walking between the bit of Parson’s Road that is on the border between Pembroke and Devonshire). Lynne Winfield, however, proposes that this would have been ‘an easy 45-minute walk in those days as the crow flies’.

Mary Ball, however, did live in Smith’s – according to the genealogy websites she was connected to the Peniston family and her land in Smith’s was adjacent to the south shore close to Spittal Pond. However all her slaves are documented to be male.

Grafitti inside Jeffrey’s Cave. Photo: Climbderock.

The Royal Gazette from 15 July 1834 contains a report about Benjamin Patty’s slave ‘Jeffery’, who along with another of Patty’s male slaves, Syke, was sentenced to 10 days imprisonment including hard labour on the treadmill and solitary confinement. Their crime was reported to be an attempt to rescue a runaway slave called Daniel, property of Charles Taylor of Smith’s Parish. This rescue attempt was said to have occurred in Hamilton. Both ‘Jeffry’ and Syke are also listed in the 1821 slave register. At that time ‘Jeffry’ was 10 years old and was owned by Thomas Tuzo of Hamilton. Syke was owned by Thomas’s brother, Captain Henry Tuzo and the Tuzo family had multiple slaves, both male and female, but their lands appear to have been in the Hamilton and Point Shares areas, so not close to Spittal Pond.

Royal Gazette archive.

So which one was the Jeffrey of the legend? Is the Jeffrey in the above two stories one and the same? I consulted Lynne Winfield of Citizens Uprooting Racism in Bermuda (CURB), researcher and editor of CURB’s publication Black History in Bermuda: Timeline Spanning Five Centuries, who was very helpful with information and suggestions for research. She believes that the real Jeffrey is the one owned by Benjamin Patty and he certainly had form in this particular area on the basis of the 1834 report. Cyril Packwood’s book, Chained on the Rock, also details both of the above stories of ‘Jeffrey’ consecutively. He doesn’t make a direct connection between the two stories although this is implied.

The records of the Slave Compensation Commission, set up to manage the distribution of the £20 million compensation for slave owners following emancipation, provide a more or less complete census of slave-ownership in the British Empire in the 1830s. According to the centre for the studies of the legacy of British slavery, Benjamin D Patty of Pembroke was awarded £78 compensation for his three slaves in 1836. Of course, the newly-freed slaves received nothing financially in compensation, and emancipation was followed by Jim Crow-type laws, segregation, and the structural racism that persists today.

Jeffrey could have come from an earlier time or his name might have been something else. Folklore legends are based in reality but facts become distorted in the re-telling of the story over the generations. In the course of my research, one of the Bermuda archivists thought that the story of Jeffrey of the cave coincided with that of Sally Bassett, a female slave who was executed by burning at the stake in 1730, but the historical material in the archives from the 18th century is nowhere near as detailed as the 19th, so there is no written evidence (that I could find) to substantiate this.

Delving into the online resources, especially the Royal Gazette archives and trawling through the records at the Bermuda National Library and the Bermuda Archives was an eye-opening experience as to the legacy of slavery.

Probably the most famous slave narrative to come out of Bermuda is that of Mary Prince. Her autobiography, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, was the first such account to be published in England by a female slave in 1831. Every time I drive along St John’s Road in Bermuda (usually to go to the hardware store) I look up that blue house on the hill and think of her. This was the house that she describes in her book:

‘The house was large and built at the bottom of a very high hill… the stones and the timbers were the best things in it; they were not so hard as the hearts of the owners.’

School Lands Lane in Pembroke. Photos Climbderock.

Mary’s book drew public attention to the continuation of slavery in the Caribbean, despite an 1807 Act of Parliament officially ending the slave trade, and was a powerful rallying cry for emancipation which eventually occurred in 1834. In her book Mary describes the punishments inflicted on her:

‘To strip me naked – to hang me up by the wrists and lay my flesh open with the cow skin [whip], was an ordinary punishment for even a slight offence.’

She also describes the brutal flogging of a fellow pregnant slave, Hetty, who subsequently delivers a still born child and then herself dies after further floggings. Mary ran away from her owners to her mother, who had joined Richard Darrell’s household at Cavendish:

‘After this I ran away and went to my mother, who was living with Mr Richard Darrell… She dared not receive me into the house, but she hid me up in a hole in the rocks near, and brought me food at night, after everybody was asleep. My father, who lived at Crow Lane, over the salt water channel, at last heard of my being hid up in the cavern, and he came and took me back to my master.’

According to Lynne Winfield, research carried out by Dr. Margot Maddison MacFayden points to the cave Mary Prince hid in as likely being located on what is now the property of Cavendish Heights condos: ‘The original old house on the property has been converted into a townhouse but the hillside has been cut into and only a small part of the cave remains… more like a substantial indentation in the rock, what was probably the back of the original cave.’

***

I cycle around the landscaped and manicured grounds of the condos and try and picture it back in Mary’s day. I don’t find the potential new bouldering area that my imagination had conjured up, and there are no caves visible. There are some obviously quarried rock outcrops and ‘indentations’, many of which could be the remnant of Mary’s cave.

***

It was, apparently and unsurprisingly, common for slaves to run away from their masters. There was even a medical diagnosis for this behaviour: Drapetomania. This was coined by American physician Dr Samuel Cartwright (1793–1863) whose middle name was, appropriately enough, ‘Adolf’.

Samuel Cartwright.

According to Google translate ‘drapetis’ in Greek means ‘runaway’ so I presume this is from where he derived the name and shows that, at least, he knew his Greek. Cartwright was charged with investigating ‘the diseases and physical peculiarities of the negro race’ by the Medical Association of Louisiana. His report was delivered as a speech at its annual meeting and published in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal in 1850.

Cartwright’s hypothesis centred around his belief that slavery was such an improvement upon the lives of slaves that only those suffering from some form of mental illness would wish to escape. Cartwright invoked mainly biblical arguments to buttress his opinion. His recommended treatment was, ‘whipping them out of it, as a preventive measure against absconding, or other bad conduct. It was called whipping the devil out of them’.